Feliz Día de San Valentín to all my readers. In Mexico, Valentine’s Day is often referred to as Día del Amor y la Amistad (Day of Love and Friendship).

Feliz Día de San Valentín to all my readers. In Mexico, Valentine’s Day is often referred to as Día del Amor y la Amistad (Day of Love and Friendship).

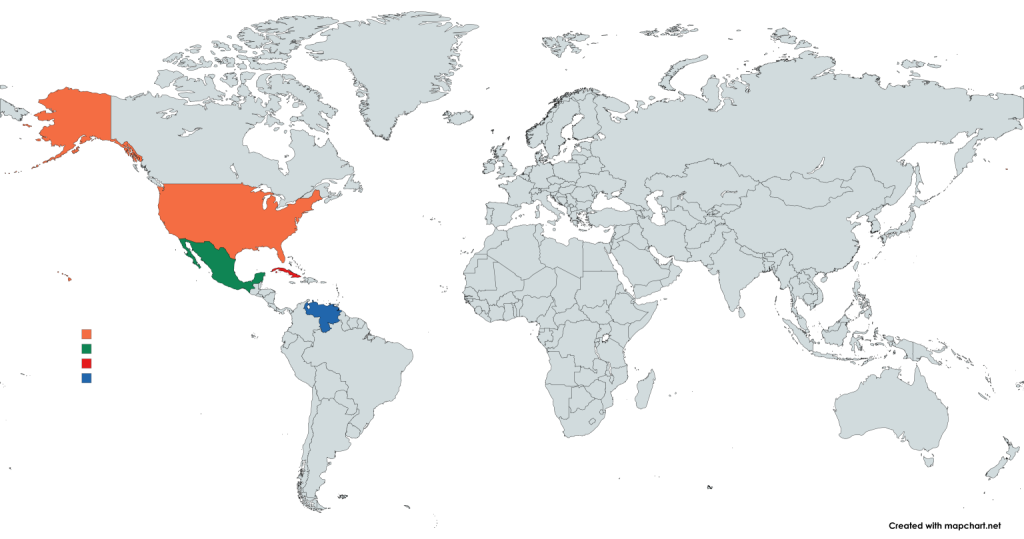

The two Mexican ships taking aid to Cuba mentioned in an earlier article have arrived to Havana, Cuba. (See Mexico Sending Aid But Not Oil to Cuba).

From NBC: “Two Mexican navy ships laden with humanitarian aid docked in Cuba on Thursday [February 12th] as a U.S. blockade deepens the island’s energy crisis.

One of the Mexican Navy ships that went to Cuba was the Papaloapan. Here it is,

What sort of aid was on the ships?

“The Mexican government said that one ship carried some 536 tons of food including milk, rice, beans, sardines, meat products, cookies, canned tuna, and vegetable oil, as well as personal hygiene items. The second ship carried just over 277 tons of powdered milk.”

Trump’s oil blockade on Cuba continues.

“The [Mexican] ships arrived two weeks after U.S. President Donald Trump threatened tariffs on any country selling or providing oil to Cuba, prompting the island to ration energy in recent days.”

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum plans to send more aid.

“Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum said Thursday that as soon as the ships return, ‘we will send more support of different kinds.’ Her administration noted that it still plans to send 1,500 tons of beans and powdered milk. Sheinbaum has previously said the humanitarian aid would be sent while diplomatic maneuvering to resume oil supplies is underway.”

If you’re planning to fly to Cuba, you’d better have enough fuel to fly out of the island, because foreign planes cannot refuel on the island

“Cuban aviation officials warned airlines earlier this week that there isn’t enough fuel for airplanes to refuel on the island. On Monday [February 9], Air Canada announced it was suspending flights to Cuba, while other airlines announced delays and layovers in the Dominican Republic before flights continued to Havana. The cuts in fuel are expected to be another blow to Cuba’s once thriving tourism economy.”

The U.S. government is sending humanitarian aid to Cuba via the Catholic Church.

NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day of February 8th, 2026, shows a sunspot visible above a hill in Zacatecas. Here it is:

From the NASA caption: “Explanation: An unusually active sunspot region is now crossing the Sun. The region, labelled AR 4366, is much larger than the Earth and has produced several powerful solar flares over the past ten days. In the featured image, the region is marked by large and dark sunspots toward the upper right of the Sun’s disk. The image captured the Sun over a hill in Zacatecas, Mexico, 5 days ago. AR 4366 has become a candidate for the most active solar region in this entire 11-year solar cycle. Active solar regions are frequently associated with increased auroral activity on the Earth. Now reaching the edge, AR 4366 will begin facing away from the Earth during the coming week. It is not known, though, if the active region will survive long enough to reappear in about two weeks’ time, as the Sun rotates.”

Trump’s noose is tightening on Cuba and Mexico is not sending oil there. (See here and here).

From the New York Times: “When President Trump declared a ‘national emergency’ last month, accusing Cuba of harboring Russian spies and ‘welcoming’ enemies like Iran and Hamas, it came with a warning: Countries that sell or provide oil to the Caribbean nation could be subject to high tariffs. The threat seemed to be directed at Mexico, one of the few countries still delivering oil to Cuba.”

Since communism was installed in Cuba in 1959, Mexico has maintained a close relationship with the island.

“Mexico and Cuba’s long alliance — rooted in economic and cultural cooperation and a shared wariness of U.S. intervention — survived and even deepened after the Cuban Revolution, when Mexico preserved ties with Havana even as much of the region aligned with Washington.”

On the other hand, Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum doesn’t want to endanger Mexico’s trade with the United States.

“Ms. Sheinbaum now faces a fraught balancing act: upholding her country’s historical alliance with Havana, while managing its vital yet increasingly tense relationship with the United States.”

So how is President Sheinbaum squaring that circle?

“The Sheinbaum administration has been careful not to provoke Mr. Trump, who has strained Mexico’s economy with tariffs and threats of military action to stop fentanyl from crossing the border. He has also threatened to withdraw from the free trade deal with Canada and Mexico, the U.S.’s largest trading partner.”

So Sheinbaum is sending aid to Cuba but is now not sending oil.

“Ms. Sheinbaum has largely held to her country’s commitment to Cuba, a Communist country, where people are struggling with surging food costs, constant blackouts, a lack of critical medicine and dwindling fuel. But Mexico has not sent any oil to Cuba since early last month.”

“ ‘No one can ignore the situation that the Cuban people are currently experiencing because of the sanctions that the United States is imposing in a very unfair manner,’ she said during a news conference on Monday [November 9th]. She added that Mexico had deployed two Navy ships carrying more than 814 tons of humanitarian aid — mostly staple foods and hygiene supplies — to Cuba.”

“Cuba, whose main oil provider was Venezuela, has faced chronic fuel shortages for years, but the situation has become far more severe since last month, when President Trump took control of Venezuela’s oil supply. He halted deliveries to Cuba, which now only has a fraction of the oil it needs.”

“Mexico had been sending about 22,000 barrels a day, but that figure dropped to about 7,000 toward the end of 2025 — which was still far less than Venezuela was sending, according to Jorge Piñon, a University of Texas oil expert who tracks the shipments closely. The last delivery from Mexico arrived in early January, he said, days after President Nicolas Maduro of Venezuela was captured by U.S. forces.”

“To navigate the crisis, Ms. Sheinbaum has tried to distinguish between commercial contracts between Mexico’s state-owned oil company Pemex and the Cuban government, and humanitarian aid, which she insists must continue. She has also called for diplomatic talks between Mexico and the United States, and has offered her country as a mediator for discussions between Washington and Havana.”

Stay tuned for where this leads.

It’s time for the 2026 Winter Olympics, in Italy. It’s known as the Milano Cortina 2026. The opening ceremony is February 6th, but competition actually began on February 4th.

Mexico is fielding its biggest Winter Olympics team since 1992, with five competitors. Mexico has never won a Winter Olympics medal.

CROSS-COUNTRY SKIING (Esquí de Fondo) – Allan Corona and Regina Martinez.

Regina Martinez is a doctor.

ALPINE SKIING (Esquí Alpino)- Mother and Son Sarah Schleper and Lasse Gaxiola.

Colorado-born Sarah Schleper is 47 years old and has participated in six Winter Olympics, four for the U.S. and two for Mexico. Sarah is married to Federico Gaxiola and their 18-year old son is Lasse Gaxiola, the other competitor in Alpine Skiing for Mexico.

FIGURE SKATING (Patinaje Artístico) – Donovan Carrillo, who participated in the 2022 Winter Olympics.

Here is President Claudia Sheinbaum with 4 of the 5 Olympic competitors.

Donovan Carrillo, Regina Martinez, Claudia Sheinbaum, Sarah Schleper, Allan Corona

Source MOISÉS PABLO/CUARTOSCURO.COM

In a recent article I reported the case of Ryan Wedding, a Canadian snowboarder in the 2002 Winter Olympics who is now in U.S. custody, accused of being a major drug trafficker with the Sinaloa Cartel.

From the Toronto Star: “Ryan Wedding walked into a California courtroom with a sneer, eyeing investigators in the front row and a swarm of journalists packing the gallery. Once a top FBI fugitive, Wedding finally faced a U.S. judge in federal court this week, where he pleaded not guilty to 17 felony charges — including murder, drug trafficking and other alleged crimes…Mexican and American authorities had cast a wide dragnet to catch the fugitive, and now they have their target. Still, many of the biggest mysteries in this unfolding crime story remain unanswered.”

The U.S. and Mexican governments publicly disagree about how Wedding was arrested.

“Wedding’s capture has become a major diplomatic flashpoint between two governments. At issue: What exactly did U.S. agents do inside Mexico? According to Mexican officials, Wedding voluntarily surrendered himself to the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City. If you ask American law enforcement leaders, and Wedding’s lawyer, they’d tell you that’s wrong; he was nabbed in what the FBI Director Kash Patel has called a “high-stakes” tactical operation by U.S. agents. The problem is that from the Mexican perspective, the FBI isn’t supposed to be operating on Mexican soil. Mexico’s President Claudia Sheinbaum has challenged Patel’s description, saying her government would never allow a foreign power to execute such an operation…While the FBI has declined to share more details about the nature of his arrest, the Wall Street Journal has reported that Mexican security forces were closing in when they were joined by U.S. authorities who, following an intense negotiation, apprehended Wedding. It remains unclear if we’ll ever learn the truth.”

Interestingly, FBI Director Kash Patel was in Mexico City when Wedding was detained. And how about this photo of U.S. Ambassador to Mexico Ron Johnson, Mexican Security Secretary Omar Garcia Harfuch, and FBI Director Kash Patel, together?

So how was Ryan Wedding actually taken into custody?

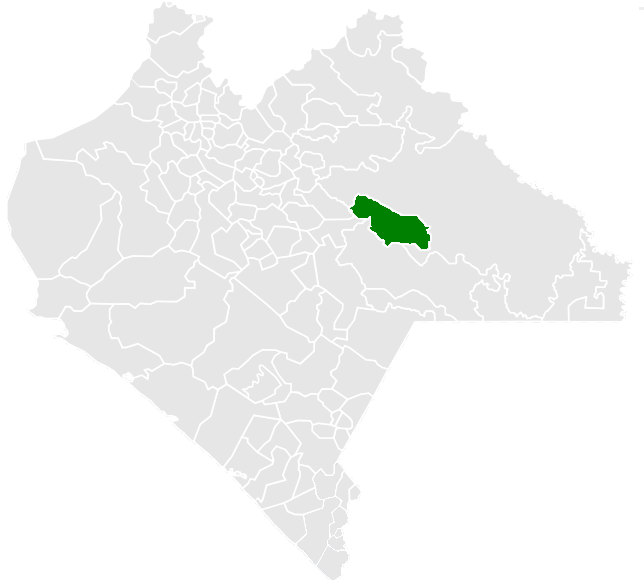

Excelsior reports a thriving business in the state of Chiapas (bordering Guatemala) of selling fake birth certificates to foreigners.

From Excelsior: “Authorities of Chiapas are investigating a network dedicated to the trafficking of birth certificates for foreigners in 12 border municipios, an operation that has resulted in 3 detentions…”

In Mexico, a municipio is a city or town with the area around it, and the jurisdiction of that government.

“…[T]he investigation began after irregularities were detected in the public registry of the Tzimol municipio..

So what foreigners are they selling them to?

“...[T]hese birth certificates are principally sold to citizens of Cuban and Haitian origin. The costs of the documents range from 1,500 to 2,500 dollars apiece.”

The article says “citizens of Cuban and Haitian origin”. It must mean Cuban citizens and Haitian citizens currently in Mexico. If they were Mexican citizens of Cuban or Haitian ancestry why would they want fake birth certificates? After all, the article calls them “foreigners” and the caption of a photo refers to “Haitian migrants”.

In the municipio of Altamirano they discovered over 1000 of these fake birth certificates in the registry system, and they didn’t even have signatures or fingerprints.

More than a dozen municipios in the border area are being investigated, and it’s supposed that public officials in public registries are involved.

In a recent article I reported that Mexico is Cuba’s Biggest Oil Supplier and Trump is OK With That.

That may be about to change.

From the Associated Press: “Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum said Tuesday [January 27] her government has at least temporarily stopped oil shipments to Cuba, but struck an ambiguous tone, saying the pause was part of general fluctuations in oil supplies and that it was a ‘sovereign decision’ not made under pressure from the United States.”

That’s a little hard to believe.

“Sheinbaum was responding to inquiries on whether the state oil company Pemex had cut off oil shipments to Cuba in the wake of mounting pressure from U.S. President Donald Trump that Mexico distance itself from the Cuban government, though U.S. officials have not publicly requested that Mexico stop the oil.”

“ ‘Pemex makes decisions in the contractual relationship it has with Cuba,’ Sheinbaum said in her morning news briefing. ‘Suspending is a sovereign decision and is taken when necessary.’ ”

“Sheinbaum’s vague statements come as Trump has sought to isolate Cuba and further ramp up the pressure on the island, a longtime adversary under strict economic sanctions from Washington. Trump has said the Cuban government is ready to fall, and that the island would receive no more oil shipments from Venezuela after a U.S. military operation deposed former Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.”

Mexico has had close relations with Cuba ever since the communist takeover in 1959. One reason, I believe, is for Mexico to demonstrate its independence from the United States. It certainly doesn’t profit much from it.

When I visited Cuba in 2014, I hardly saw any Mexican products for sale.

The Mexican government is well aware that trade with the U.S. is much more profitable than its relationship with Cuba.

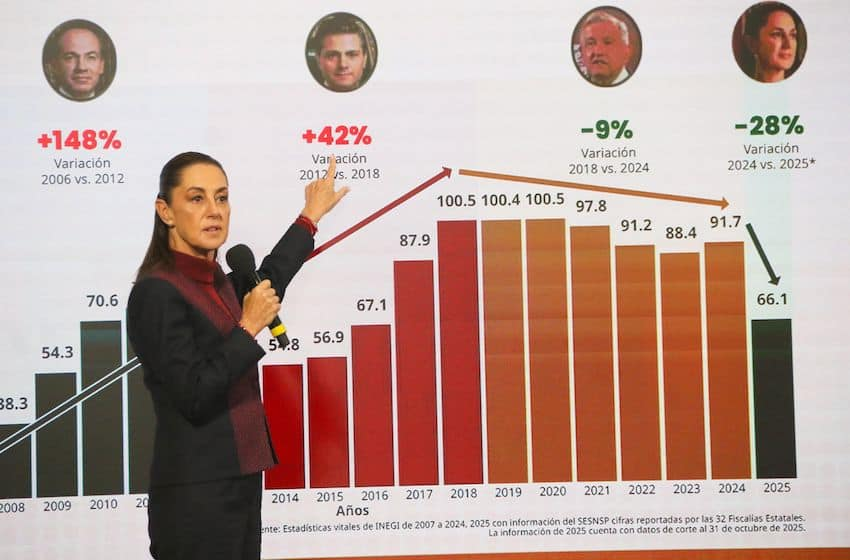

According to the Mexican government, the Mexican murder rate went down in 2025. Is that correct?

Peter Davies of Mexico News Daily dealt with this issue in his January 26th article entitled Is security in Mexico improving or are the numbers being manipulated?

From the Mexico News Daily article: “On Jan. 8, the federal government presented preliminary statistics that showed that homicides declined 30% in 2025 compared to the previous year. At face value, it certainly appears to be good news, even though homicide numbers in Mexico remain high, with more than 23,000 victims reported last year. Standing next to a bar graph, Sheinbaum frequently lauds the sustained reduction in murders as a testament to the effectiveness of her government’s security strategy; on Jan. 8, she highlighted that the murder rate in 2025 was the lowest since 2016.”

So why is there skepticism about those figures?

“However, there is a growing skepticism about the accuracy of the government’s numbers. On one hand, there are concerns that authorities in Mexico’s 32 federal entities are not accurately reporting homicides because they are incorrectly classifying some murders as less serious crimes. On the other hand, there are claims that the decline in homicides during Claudia Sheinbaum’s presidency is related to an increase in disappearances. It’s not the first time that homicide numbers touted by a government led by Sheinbaum have been called into question. That also happened when the current president was mayor of Mexico City, from 2018-2024.”

What is the source of the Mexican federal government’s statistics?

“The homicide data the federal government presents on a monthly basis is derived from reports it receives from the Attorney General’s Offices in Mexico’s 31 states and Mexico City.”

And…

“The reliability of the statistics the state-based Attorney General’s Offices provide to the Executive Secretariat of the National Public Security System is considered by many to be questionable. ‘State Attorney General’s Offices don’t work in a vacuum,’ Alberto Guerrero Baena, a public security consultant and academic, wrote in a column published by the news outlet Expansión on Jan. 9. ‘They operate under budgetary, political and media pressures. When a homicide is difficult to prove or requires lengthy investigation, there is an incentive to reclassify it as injury, accidental death or a lesser crime,’ he wrote. ‘… An unresolved homicide looks bad in the statistics. A [fatal] injury unrelated to homicide looks better,’ Guerrero wrote.”

Guerrero gives examples of a couple of states.

“He [Guerrero] said that ‘in states such as Jalisco, where multiple cartels operate, and Chihuahua, where violence is structural, these practices of reclassification are systematically documented by independent organizations.’ “

There are other sources.

“ ‘The official statistics show declines [in homicides] while defense lawyers, forensic doctors and journalists document that violent deaths continue,’ Guerrero wrote.”

As for Sinaloa state:

“Sinaloa, one of Mexico’s most violent states and the epicenter of a battle between rival factions of the Sinaloa Cartel, is an example of another state where the incorrect classification of homicides appears to be taking place.”

The article quotes the NGO Causa en Común:

“In a report published last November under the title ‘La Transformación de los Asesinatos en Propaganda‘ (The Transformation of Murders into Propaganda), the non-governmental organization Causa en Común also wrote about the ‘possible/probable reclassification’ of homicides as other crimes. ‘Adjacent to the category of intentional homicide, there are two other categories whose behavior has been peculiar in recent years: culpable homicide (accidents) and “other crimes against life and integrity,” states the report. ‘… In the past six years, the number of victims recorded in the category of intentional homicide has supposedly declined 11%. In contrast, the number of victims of culpable homicide and ‘other crimes against life and integrity’ has increased 11% and 103%, respectively,’ the NGO said.”

There’s another report.

“A June 2025 report by Ibero University similarly flags the ‘reclassification of crimes’ as a possible ‘common strategy to reduce the visibility of high-impact crimes.’ ”

According to the Ibero report, “the apparent reduction in homicide numbers doesn’t necessarily imply a real decrease in violence, but [could indicate] a sophisticated concealment of [intentional homicide] victims through [their classification in] other categories such as disappearances, atypical culpable homicides, unidentified deceased persons or bodies hidden in clandestine graves.”

Then there’s this:

“In an interview with the EFE news agency last November, Armando Vargas, the coordinator of the security program at the think tank México Evaluá, said that to speak of a significant decline in homicides ‘is politically very profitable.’ However, he too noted that other ‘forms of violence’ have increased, ‘amplifying suspicions’ that criminal data is being manipulated. ‘The expert,’ EFE reported, highlighted that ‘some entities record more deaths from accidents (homicidio culposo) than from homicidio doloso [intentional homicide], without there being public reports of mass accidents that justify this anomaly.’ ”

Then there are the disappearances.

“A total of 34,554 people were reported as missing in 2025, according to data on Mexico’s national missing persons register. In Sheinbaum’s first 12 months in office — Oct. 1, 2024 to Sept. 30, 2025 — 14,765 of the people reported as missing in the period remained unaccounted for when the president completed the first year of her term. That figure represents an increase of 16% compared to the final year of Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s presidency, and an increase of 54% compared to the annual average during AMLO’s six-year term. Is this increase in disappearances related to the decrease in homicides? According to many observers, the answer is yes. Reuters reported on Jan. 8 that government critics claim that the increase in ‘forced disappearances’ is ‘masking the violence in the country.’ ”

“In an opinion article published by The New York Times in December, Ioan Grillo, a Mexico-based journalist with extensive experience reporting on organized crime, wrote that ‘opposition figures’ assert that the reduction in homicides is ‘just because cartels are now disappearing more people, rather than leaving corpses to be counted.’ ”

But if you add up the figures…

“If the number of homicide victims in the first year of Sheinbaum’s presidency is added to the number of disappearances in that period, the total is 40,265.”

And…

“That figure represents a decline of just 5% compared to the average annual combined total of homicides and disappearances during López Obrador’s six-year term. It represents a significant increase compared to the average number of homicides and disappearances annually in the sexenios (six-year terms) of Enrique Peña Nieto (2012-18) and Felipe Calderón (2006-12).”

Definitely, there are things about these stats that bear looking into.

Alberto Guerrero Baena, public security consultant and academic has four suggestions to improve the federal government’s statistics:

According to Guerrero, these four steps “are just the beginning of a necessary transformation.”

Here’s a bizarre story, of a former Olympic snowboarder from Canada who allegedly became a drug lord in Mexico and is now in U.S. custody.

Ryan Wedding is a Canadian Olympic snowboarder allegedly turned drug kingpin, but his crime career is over for now. Wedding turned himself in at the U.S. embassy in Mexico City and is now in the U.S. awaiting trial.

You may have wondered about the surname “Wedding”, I hadn’t heard it before. It actually derives from a place called “Wadding” in Yorkshire, England.

Ryan James Wadding was born in Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada, in 1981 and competed for Canada at the 2002 Winter Olympics (Salt Lake City) as a snowboarder.

After that, Wedding became a drug trafficker and made quite a name for himself, winding up in Mexico in the Sinaloa Cartel.

Wedding ran an operation transporting cocaine from Colombia through Mexico to the U.S. and Canada. His operation would move it by truck from Mexico to Los Angeles.

By 2005, Wedding made it to the FBI Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list.

Wedding’s FBI wanted poster reads “Ryan James Wedding is wanted for allegedly running and participating in a transnational drug trafficking operation that routinely shipped hundreds of kilograms of cocaine from Colombia, through Mexico and Southern California, to Canada, and other locations in the United States. Additionally, it is alleged that Wedding was involved in orchestrating multiple murders in furtherance of these drug crimes.”

The Canadian drug lord used the aliases “James Conrad King” and “Jesse King”, as well as a number of colorful nicknames: “Giant”, “Public Enemy”, “Boss”, “Buddy”, “Grande”, “El Jefe”, “El Guerro” and “El Toro”.

On January 22nd, 2026, Wedding turned himself in at the new billion-dollar U.S. embassy in Mexico City. Negotiations had been going on several weeks previous.

So why did he turn himself in and what does the deal consist of? Is Wedding going to rat out a lot of other people?

Another curiousity is that the day he turned himself in, FBI Director Kash Patel was at the U.S. embassy in Mexico City, on an unpublicized visit. Hmm, that’s interesting.

Here’s a photo of U.S. Ambassador to Mexico Ron Johnson, Mexican Security Secretary Omar Garcia Harfuch, and FBI Director Kash Patel.

On the 23rd, Wedding was flown to California (landing in, coincidentally, Ontario, California) to face charges on cocaine trafficking and murder.

Let’s see how this case turns out.